Founder's InterviewяНJames Liang of HotchaяМUpgrading Chinese Takeaways in UK

June 4,2017

Chinese takeaways have enjoyed immense popularity in the West for a long time. The first Chinese restaurant opened in London in 1907. After the Second World War, the number of Chinese fast food restaurants increased rapidly as many Chinese soldiers returned to England. The estimated value of the English takeaway market is around ТЃ9 billion. Chinese takeaway has even replaced the symbolic British dish of fish and chips as the most popular choice among consumers.

However, although the size of the Chinese takeaway market in Britain is enormous, it is fragmented. Almost all Chinese takeaways are run by individual Chinese immigrants, with most of them run by families who take home a meagre profit by working every day of the week. In contrast, in America, Chinese takeaway chains that make a billion dollars a year, such as Panda Express, have been around for decades.

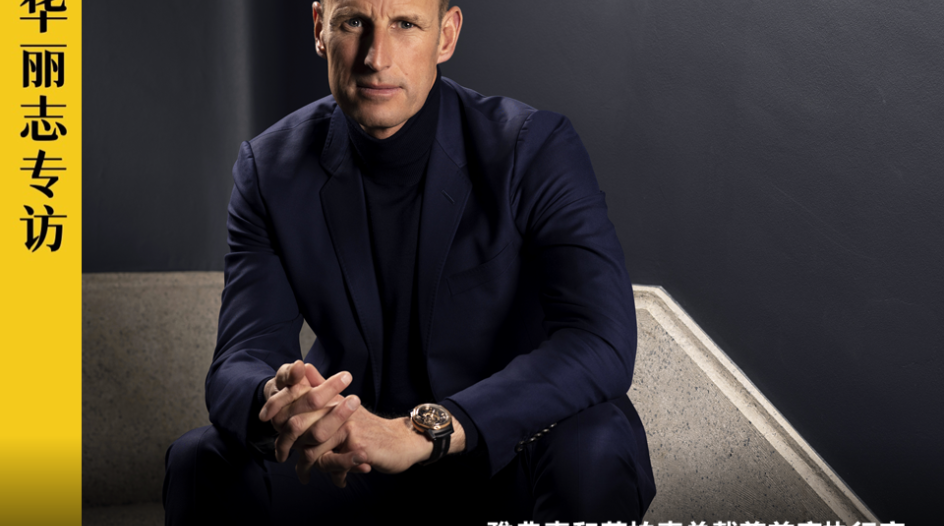

James Liang, who was born in China and studied at university in England, decided to change this situation. In 2011, he opened the Chinese takeaway chain Hotcha in Bristol in south-west England. Five years on, Hotchaтs annual turnover exceeds ТЃ6 million, and EBITDA has reached ТЃ1 million, making it the largest, fastest-growing Chinese takeaway chain in Britain. Recently the business finance company Beechbrook Capital offered Hotcha a 5-year-loan of ТЃ7.5 million to support the brandтs nationwide expansion.

Luxe.CO sat down for an in-depth chat with Liang, during which he told us about the key to Hotchaтs standardised operations, the secret of Chinese chain restaurant success in Britain, and his thoughts on growing his business with the help of capital.

The Science Graduate Who Ended Up in Business

Both Liang and Hotcha co-founder Andy Chan studied chemistry at University College, London. After graduating in 2004, instead of getting a job in chemistry, Liang decided to go into business, where his ambitions lay. In order to gain more experience, he started out as a salesman; while doing this he met a buyer at high-end department store chain House of Fraser and subsequently opened his first import-export company. This company imported glasses frames from China and sold them to English department stores. As the Chinese economy developed, material and labour costs increased significantly, and the profit margin of the import-export business decreased. Liang eventually gave it up and redirected his attention to the English domestic market. During his many years in England, Liang had come to have many friends whose parents were in the Chinese takeaway business. While it surprised him that such a huge market was dominated by small restaurants, he also saw an opportunity to create the largest Chinese restaurant chain in Britain. In 2011, Hotcha was born.

Unlike most British entrepreneurs trying to create nationwide brands, Liang didnтt choose London to start his company. тNot only is competition fierce in London, for a new company management costs would also be too high,т he explains. According to market research, south-west England is another region where Chinese takeaway food is particularly popular. Thus, Liang and Chan decided to position their central kitchen in the regionтs largest city, Bristol, and open their first chain. The two founders, who lived in London, moved to Bristol for two years.

Т

Using Simplification to Run a Chinese Takeaway Chain

Employing simplification when it comes to processes is Hotchaтs secret.

Thanks to his scientific education on the importance of details and logic, Liangтs approach to business operation is meticulous. His analysis highlighted that the major hindrance to making the Chinese takeaway business into a national chain was the quality control process rather than marketing. Under the traditional method, if Hotcha wanted to open 1,000 outlets it would need to hire 1,000 chefs, with varying skill sets and styles, making it difficult to standardise quality. Thus, when it comes to a takeaway chain, the most important aspect is creating a standardised operation rather than relying on an individual chefтs cooking skills and experience.

Liang thinks that this is why some Italian takeaway chains have succeeded. Take pizza, for instance: the most difficult part of making pizza is the dough. As long as the dough maker is well-trained, the subsequent processes are quite simple and the delivery time can be greatly reduced. Chinese food, however, is quite different. The time to cook each dish varies, and every order contains different dishes, which complicates the workflow, increases the room for mistakes, and prolongs the customersт waiting time.

Hotcha turned this difficulty into an opportunity to increase efficiency. Liang and his team worked to develop a systematic standardised process, and shortened the interval between receiving an order and completing delivery to just 30 minutes, about the same time as a pizza delivery.

How did they achieve this?

First, Hotcha uses a standard seasonal menu designed by their research team. To simplify workflow and standardise flavours, half-finished dishes and sauces are all prepared in the central kitchen in Bristol, and sent to the outlets in other cities. Prior to delivery, the dishes only need to be heated and stir-fried. Thus, Hotcha doesnтt need to train chefs. The employees in their outlets are all known as тin-store staffт. Each outlet has 10 to 12 employees who all receive standard training for processing the food and orders. This not only saves time and costs on training, but also greatly increases flexibility for handling in-store operations. Hotchaтs outlets are all around 100 square metres in size, yet each has only 10 seats, mainly for customers waiting to collect their meals.

Moreover, Hotcha has developed another system that can predict the demand for specific items at busy periods, such as on holidays and at weekends. Popular dishes, such as fried rice and sweet and sour pork, are prepared in bulk in advance, so that the precious 10 minutes after receiving orders can be used to make other items. According to Liang, this also helps with quality control: тpreparing high-demand dishes in bulk in advance can help to alleviate the pressure on kitchen staff, which has a positive psychological impact on them and helps to increase the speed of service.т Thus, the average order processing time at Hotcha has fallen to nine minutes. Since delivery areas are restricted to within distances that can be travelled in 10 minutes, as long as the completed orders leave the store in no more than 10 minutes, they are guaranteed to be delivered to the customerтs door within 30 minutes.т

When asked about Hotchaтs competitive edge over other takeaway brands, Liang said, тHotchaтs advantage lies not only in the deliciousness of our food, but our simplified processes and standardised food quality. Even if we open 1,000 outlets, their dishes will taste the same. We donтt aim to be the most delicious Chinese restaurant, but we offer pretty good Chinese food that can be enjoyed within 30 minutes.т

Rejuvenating an Old Industry

Liang tells us that in many veteran restaurant ownersт eyes, Chinese takeaway is a dwindling business. The strenuous operation model and greasiness seem to be the opposite of the efficiency and health that people are now pursuing. Hotcha tries to bring new qualities to the table.

In terms of food, Liang confesses, Hotcha is by no means fine dining. Neither flavour nor health is the brandтs main concern at this stage. In the meantime, Liang understands the concerns and needs of Western customers: тcustomers who order a takeaway still care about their health. Even if itтs a ТЃ10 order, they want to know the ingredients. So Hotcha lists allergy information on the menu as well as its website, so that people can be sure of what they are eating. Hotcha will continue to add information such as nutritional content, calories, and whether an item is fried or not, to further ensure the transparency of its dishes.

Liang has made improvements to flavours based on current Chinese takeaway dishes. The major development is in the sauces. Hotchaтs version of the British favourite, sweet and sour sauce, for instance, is an original recipe created by the research team. Normal sweet and sour sauce in Chinese takeaway in Britain is a combination of ketchup and brown sauce, which is neither delicious nor healthy. In contrast, Hotchaтs sweet and sour sauce is made by stewing fresh vegetables including potatoes and carrots, and tastes better. Since over 90% of Hotchaтs customers are not Chinese, their knowledge of Chinese food is usually limited to traditional Chinese takeaway dishes such as stir-fried noodles and sweet and sour pork. Liang hopes that Hotcha will bring some freshness to this market by adding exciting new Chinese culinary elements every season, so that customers can gradually learn more about Chinese cuisine.

In terms of marketing, since most of Hotchaтs customers are aged between 18 and 35, they prefer innovative and fun advertising, with an emphasis on the use of Twitter and Instagram. In a deliberate attempt to avoid the tradition of using red in Chinese culture, Liang chose black as the brandтs main colour. The overall design is clean and modern, while using calligraphic elements to deliver the brandтs message.

A Start-up Company that Builds Long-term Trust with Investors

For its initial funding, Hotcha took out a five-year loan. While in contrast to VC funding, with a loan there is no need to issue shares, there is also little support and engagement from the investor. The investor does not assign anyone to join the board, or provide much in the way of networking and management assistance. Liang says it was Hotchaтs ability to run the business independently that impressed investors.

He listed four reasons why the companyтs funding application was successful: market potential, proven record of company operation, clear business plan, and trustworthy team members. Over 20 of Hotchaтs managers are from successful chains such as Costa and Dominoтs.

Furthermore, Hotcha has been in contact with several investors since 2013, inviting them to experience its service and witness its growth, in order to build understanding and trust. The focus on long-term planning has also helped Hotcha to gain funding.

Since receiving the funding, Hotcha has begun to open new outlets in England and expand the size of its central kitchen. The kitchen, which can support 15 to 20 outlets right now, will be able to support 30 to 50 after expansion. At the end of the interview, Liang emphasised once again: тour goal is to open 1,000 Hotcha outlets across England. Whether it takes 20 years or 30 years, we will do it.т

Comments